How the economic machine works: Why Financial Literacy is Your Best Defence

A summary of Ray Dalio's "How the economic machine works", plus a bit extra.

Thanks for coming here, I think you will enjoy this article. Before you start reading, if you can click the ❤️ button on this post so that other people can discover it on Substack, it really makes a big difference. And please share it. Share it on your Linkedin. Share it on your Facebook. Share it on your X. Thank you.

It's coming. We don't know exactly when. We don't know how bad it will be. But it is coming. And over time its impacts will get worse and worse, where even the cures will contribute to the eventual worst case scenario. It has happened since civilizations began and people bartered with shells. With our interconnected world, will impact our current and future societies in ways that many of us living in the "western" world cannot comprehend.

Ok so what is this thing that is coming? It's not death. It's not taxes. Well, those are coming too.

Well, it's a financial recession, friends. And when it finally comes it's going to hit us hard (As I write this there has been a drop in markets over the last few business days. For reasons that are beyond the scope of this article, I don't think we're in a recession/depression… but one will come!).

This post, and maybe a couple more, will be primarily focused on economics - in a sense our collective finances. After all, business and finance is an important part of every life.

Hopefully this serves you.

I am trying to synthesize and understand some ideas for myself here, and am a firm believer that financial literacy is a key skill that all need more of (myself included). This will not be a "learn how to budget" or "what investment is good right now" or "should I buy Bitcoins and sell Amazon" series of posts. All those things are good things, and many others do them far better than I do.

Ok. Read this. And after, watch Ray's amazing video (viewed over 39 million times as of today) which can pretty much sum up an economics degree in 30 minutes. Then come back and re-read this. All imaged below are screenshots from his video.

Here we go.

Transactions

The economy is made up of a series of transactions repeated "zillions of times". These transactions exchange cash (money) or credit for goods and services from sellers. Everyone operates this way, from governments to your local corner store to the kids selling lemonade on a summer day.

The economy is simply the sum of all transactions. Cash (money) and credit are exchanged for goods and services are the total spending in an economy.

Economy = Sum of all transactions

Credit

Sometimes, credit is used as a 1 for 1 replacement for cash. But what is it? Credit is more or less a promise of future payment of cash, usually for a bit more than what was lent. For example, I, the lender, can "credit" you $100, if you, the borrower, pay me back the money plus 10% interest, so $110, in a year (or some timeline). So it works like cash, kind of… but the key difference is that it only has value if it is honored, and you, the borrower, now have $110 of debt. And this creates some risk to me, the lender, because you may not pay me back.

Arguably, there are good and not so good uses of credit. Good uses of credit can be when the borrowed money is used to become more productive, i.e. build a business, or buy tools to make your business better. In Dalio's example, someone buys a tractor so they can plow their fields faster, so they make more money and the economy is more successful (presuming they can sell their harvested products of course).

A less good example would be buying a TV, or fancy car, or unnecessary clothing, or spending on unnecessary fancy restaurants - essentially any thing that does not bring you a return of some kind. In this case, the credit has not helped you derive more value, therefore you are taking from your future self and now have debt you need to work harder to pay back.

Why is credit so crucial? Simply put, credit empowers borrowers to spend more, that money spent, that transaction, goes in someone else's pocket and becomes their income, and spending (transaction) fuels the economy.

Person A lends money to person B. Person B spends that money to Person C (or D, E and F). So then Person C (or D, E and F) now has more money in their pocket, which in turn allows them to have more credit, and in turn, spend more than they make. And that spent money from Person C becomes the income for others, who in turn make more money and can borrow more money.

Credit = I Lend you Money now in exchange for more money later.

Once you have that money, you have debt.

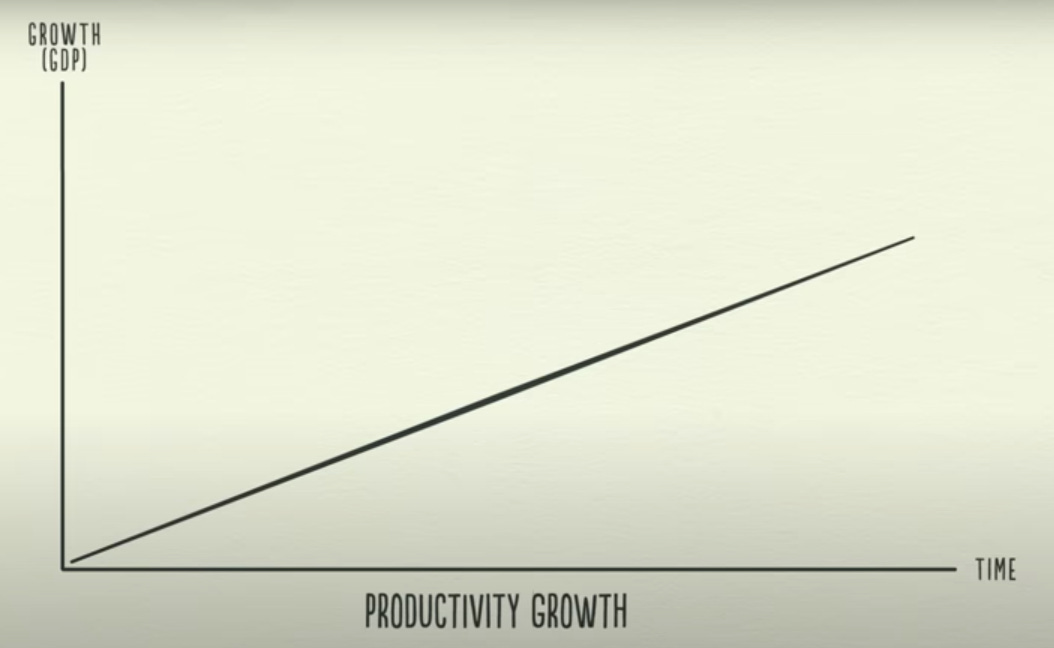

Productivity and GDP

What's productivity? You can think of it as how productive a person or company is for the input. In economic terms, it's the a ratio of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per hour of work. Essentially how much money is made per hour. So if you work 2000 hours a year, and make $40,000, your productivity is $20/hour. When you borrow money for a business, the hope is that you are going to increase your productivity to make more per year.

In macro terms, the GDP is the total $ generated by that country's economy, and the hope is to, using more knowledge, increasing population, sometimes debt, better technology, and more efficiency, make more over time, to have more productivity growth -> i.e. make more with less effort.

In reality GDP growth = Productivity growth + debt growth + population growth.

Debt Cycles

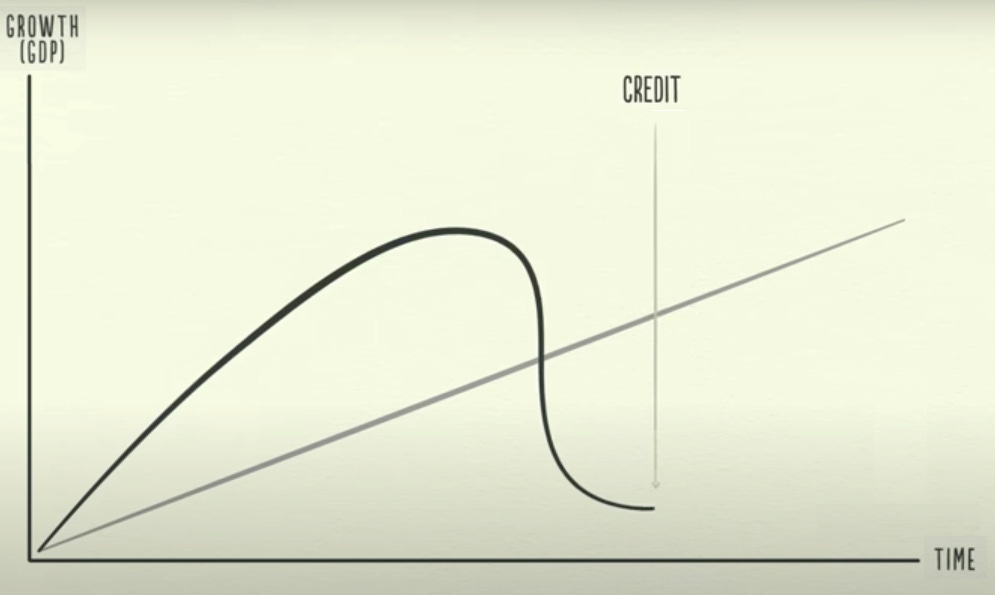

So when we borrow money, this all starts a chain reaction that, because we tend to not always spend on becoming more productive (we buy TVs and fancy cars and trips to Disneyland) sometimes means spending rises faster than productivity. Although productivity growth is crucial over the long term (think how societies have evolved from 500 years ago), the GDP benefits from credit and spending in the short term.

People and companies with good "credit" have access to more credit, and therefore spend more than the productivity they can produce, with the goal of obtaining more goods and services faster. This results with more money in the sellers pockets. Incomes go up.

Economic times are good.

And with more money in pockets, people pay more for things that have limited supply (i.e. inflation -> keep this in mind for later). With inflation, interest rates start to climb up in order to keep inflation from rising too quickly - it tempers borrowing. Additionally, as credit was so easy to get, people and companies who were not wise in their use of debt start not being able to pay back what they owe. So people can't pay money back and interest rates are going up, causing the debt payments to get bigger and bigger. People and businesses spend less on nice to haves, productivity drops, and incomes drop. As incomes drop, the economy slows down, and a recession hits.

Person A spends less, so person B has less income to use. Because person B has less income to use, he can borrow less money. On top of that, person B's debt payments are bigger than before, so he has to spend more on debt payments… and the economy slows down.

Economic times are less good. Sometimes they're outright bad. And this is sometimes called a recession as economic health is recessing. People will lose jobs, and lenders sometimes have to take back only a fraction of the debt they are owed.

At this stage government(s) have a few "standard" options to spur the economy out of the recession:

decrease interest rates (make money cheap to borrow again),

print money (also known as quantitative easing - QE), or

cut spending (i.e. implement austerity measures - the hard way out).

Reduce debt (restructure companies, sell off their assets)

Most governments will do (1) and (2), as (3) and (4) will be painful in the short term and governments that cut spending fall out of favor and do not get voted back in. This is important, keep it in mind for later.

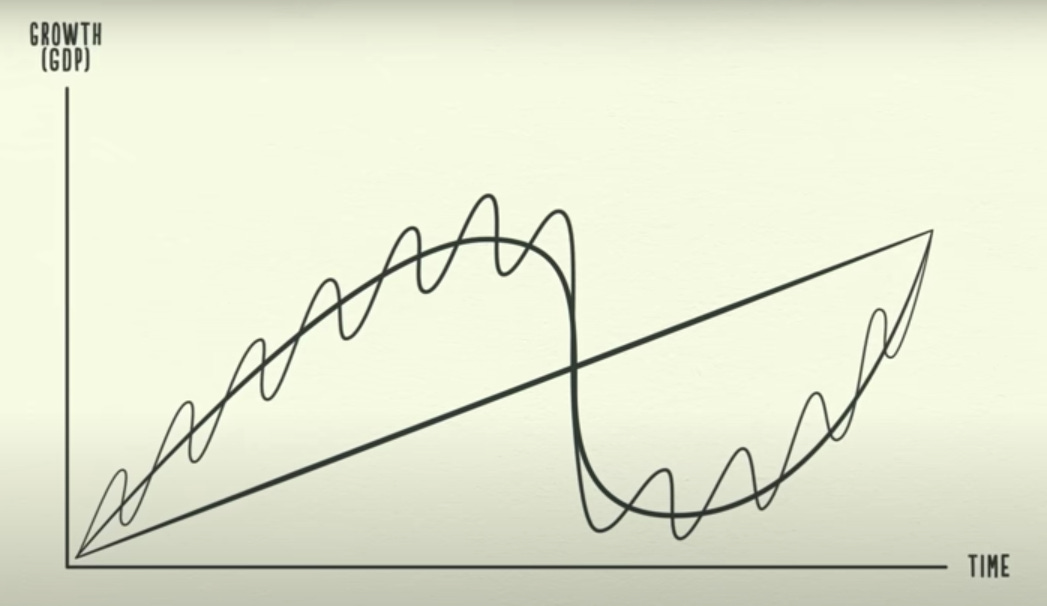

Interest rates drop, money gets printed, and people start to access credit again. The recession is over, and the whole thing starts up again. This is a short term debt cycle, and historically, occurs in 5-8 year cycles, over and over again.

When credit is easily available, there's an economic expansion.

When credit is NOT easily available, there's an economic recession.

A key thing to note here is that even though we make it through these short term cycles, we (most people, definitely governments) end up with more debt over time, and overall, more growth over time. So you borrowed some money, had a hard time for a few months, but then started making more money and are able to handle your debt (make payments), but cannot pay it all down.

Also, remember the inflation piece? Well, the money you had from 50 years ago, because of all that money printing and interest rate increasing over time, means you can buy less now with that same money than you could 50 years ago.

What happens next? Well, eventually, all the negative impacts of these short term debt cycles add up. All that debt you (or governments) amassed never went away… they just became manageable for a while. But eventually, the debts are just so huge that no matter what, they can't be paid back. So people and governments stop spending freely… except now there's a key difference in that debt is simply too big. They'll decrease interest rates, but it doesn't really help. The debts are just too big.

Long Term Debt Cycle

Overlaid on a longer 75-100 year time scale is the long term debt cycle.

Imagine it -> you borrowed so much money over the years, but your debt is now just too big, even if the interest rates on it are zero. So you stop spending on nice to haves. So there's another recession, and the government has printed even more money. So now the value of your savings is dropping and you can buy less with that money.

And it all comes to a grinding, sudden stop.

Now what?

Now what indeed.

Deleveraging

Another way to state taking on debt is to leverage. So the 75-100 years mentioned above, debts increase and the economy becomes leveraged. Now there's a point at the end of the long term cycle where economies need to (try to) deleverage - i.e. eliminate debts.

Historically, across all cultures, countries, societies (matters not the political system or financial system, sorry not sorry socialist, populist, communist advocates), this has happened using one or more of the following financial tools (similar to the short term ones available, but some differences):

cut spending (i.e. implement austerity measures - the hard way out).

Reduce debt (restructure companies, sell off their assets)

Redistribute wealth from haves to have nots

print money (also known as quantitative easing - QE)

Usually spending is cut first. Governments and people stop spending with the goal of cutting down their debts. HOWEVER, as people spend less, then other people have less income to spend on paying back debts. Businesses and governments have to downsize, and paying down the original debts is difficult and slow.

So when they can't pay back debt, lenders (such as banks) start not being able to collect, and have to start defaulting on their debts. This is a severe state and at this stage, a country is likely in a full on depression. When those lenders suddenly are not getting paid back some or most of what is owed to them, they suddenly realize that they're not as rich as they thought they were. Sometimes debts are restructured - the interest rates are decreased, or the borrower agrees to pay back less than the original amount borrowed. In summary - the lenders get less than what they are owed. But they rather get a little bit than nothing. This restructuring can cause values of assets to drop (stock market drops, the US housing crash of 2008).

During these tough times, a third option governments use is wealth redistribution. It makes sense - the people with little or nothing start to really resent the people that have money - after all, now the disparity between the upper class and the lower class is wider than before, and why are they driving around in fancy cars and eating at nice restaurants when some can't afford rent? (We may already be in this phase of resentment in Western countries - this is predictable and has happened before and will happen again). At this stage the government typically raises taxes and starts appropriating more money from those that have it to fund the programs needed to take care of the unemployed and try to stimulate the economy.

If governments can make it through deleveraging of their economies using one of these first three tools, then they're likely having undergone deflationary deleveraging - asset prices have fallen, and your dollar (or Yen, or Kronen) can actually buy more now than before. It is an extremely painful process getting there, but ultimately after this point people fare better.

The last lever governments can use in either short or long term debt cycles - money printing - can be used to offset the pain of the other three levers. As it is inflationary, it needs to be used carefully so as not to decrease the value of your money too badly. The central bank prints money, and buys financial assets through the purchase of government bonds. This move allows the government to spend on goods and services, putting money into the hands of the general public.

Printing money carefully will not cause inflation to take hold provided that the printed money offsets the loss in credit. i.e. instead of people using credit to buy something, they are now using more cash, so they have not seen a drastic increase in cash availability, therefore the value of the money does not decrease.

That's one of the main differences we (North America, and other parts of the world) had between the global 2008 and 2020 financial crises. When going through the 2008 financial crisis, the money printed offset the loss in credit, so inflation did not substantially increase. However, the money printed during 2020 COVID saw an increase on top of the available credit, so our governments contributed to the inflation that we all saw after (but it was arguably the easier path to take at the time, but that discussion can take a pause until another time). It wasn't the sole cause of inflation due to what else was happening around the world, but it sure has not helped.

Side note, but important note: Governments almost always eventually devalue their currency overt time through QE/printing money. No true currencies are left that existed 100 years ago, buying the same values of goods they bought then. It devalues currencies and, although assets increase in price when QE is occurring, they're only increasing in price, not value. Assets only gain in value if they are producing more or creating more overall, or harder to come by - like those first edition Air Jordan's one of you still has kicking around.

Key takeaways

Alright so, let's summarize everything with some key takeaways.

Economies are made up of transactions.

Transactions are exchanges of cash or credit for goods and services.

Credit can be used to borrow money from your future self, giving yourself debt.

There's good debt (used to become more productive) and bad debt (TVs, depreciating assets).

GDP growth = Productivity growth + debt growth + population growth.

Inflation happens when there's too much money available, or not enough goods and services (opposite sides of the same coin).

Deflation happens when there's not enough money available, or too many goods and services (again, opposite sides of the same coin).

As long as credit exists in a society, credit cycles happen.

There are short and long term credit cycles. The short ones last 5-8 years, and the long ones historically last 75-100 years.

Eventually, a country/economy has to deleverage their debt. This can be done by:

Cutting spending (i.e. implement austerity measures - the hard way out).

Reducing debt (restructure companies, sell off their assets)

Redistributing wealth from haves to have nots

Printing money (also known as quantitative easing - QE)

Printing money almost always devalues currencies; for some governments it happens quickly, and others it takes many decades… but it always happens. Assets protect you against this.

Finally, Ray leaves us with three rules of thumb that apply to both personal and governmental levels:

Don't have debt rise faster than income. Eventually the debt burden will crush you.

Don't have income rise faster than productivity. Eventually you'll become uncompetitive. (You'll rest on your laurels and get lazy, basking in that money. Another way to look at this → don’t fund your GDP solely through debt).

Do all you can to raise your productivity. In the long run, this is what matters most, especially on a country basis.

The truth is we are in global economies. The way we make money is by bringing value to others. It's the game we all have to play, and it is the game we have been playing since we started working together in tribes and villages.

Bring value to others and keep getting better at what you do.

There's no easy way to operate outside the system, so learn the rules of the finance game and play it to the best you can. It really matters to the health and wellbeing of your life, and how much you can contribute to others.

Thanks so very much for reading. If you loved this, please share it with your friends, family, enemies and strangers. Click the ❤️ button on this post so that other people can discover it on Substack. Read the other things I wrote. Oh and I should be asking you to subscribe if you haven’t. Please do these things, they all mean a lot.

Totally… an AGI future gets really funky!

What do you think will happen with these cycles as AI and robotics takes off over the next decade?